[ 10 ]

Applying Main Plots and Subplots to User Journeys and Flows

The Ideal Journey

Most of us have worked on a project requiring us to define key user journeys or flows. The user journeys may be either functional, focusing on what the user does, or functional-emotional, including what the user thinks and feels as well as does. Whichever format these user journeys have taken, our focus is often on a few key ones related to some of the main user goals or business objectives. Although at times alternate journeys are defined, more often than not the user journeys focus on the ideal scenario. We abstract steps or generalize what the user thinks and feels. Although these journeys at times depict that the user leaves the product or service in question to visit another website or do something offline, they most commonly focus primarily on what happens when using the product or service in question.

There is nothing wrong with that, per se, but also nothing particularly right about it either. As shown in Figure 7-2, a user’s journey rarely follows a linear path. Instead, it’s a mixture of online and offline and shifts from searching wide and far to narrow and deep. For user journeys to add the most value, they need to more accurately reflect what actually happens, or is likely to happen, no matter how complex this is. As much as we like to abstract to the ideal and the simple, the reality in which our products and services are going to be used, when and where as well as by whom, is complex, and we do best in embracing this complexity. It’s part of the beauty of what we’re designing for but also what ensures that the products and services we design actually work for people.

As with every deliverable, tool, or method we use on a project, user journeys should be used in such a way that they add the most value. At times, adding more detail won’t bring the work forward in the most valuable way for the project. It may stop key internal team members and clients from understanding and buying into what’s presented. Or, perhaps using user journeys only doubles the effort if some other more detailed work is being carried out; for example, through detailed flow diagrams.

We shouldn’t, however, shy away from adding in complexities for the fear of making things complex. Complex is, after all, an accurate description of the context in which our products will be used, and that complexity can be presented in multiple ways that are easy to understand. Adding in some of these factors that differentiate between different users (such as drivers, handoff points, touch points, key search terms, etc.) can help provide a clearer and more accurate picture of a potential user’s experience with our product or service. And at times, defining more than just the ideal and some key happy journeys is needed to really get under the hood of, and be able to account for, all eventualities. It’s by actively designing for these scenarios, too, that we make sure our product or service both supports and tells the right product experience story, no matter the outcome. This is where drawing on the concept of the main plot and subplots in traditional storytelling can really help us.

The Role of the Main Plot and Subplots in Traditional Storytelling

In traditional storytelling, more than one storyline often runs through and makes up the narrative. Just think of, for example, The Lord of the Rings: the main story revolves around Frodo going back with the ring, but at the same time minor stories take place around the adventures of Legolas and Aragorn who are trying to protect settlements while destroying the Orc armies. Another storyline revolves around Merry and Pippin and their escape from the Orcs. All three of these minor stories, which weave into the main plot by the end, are called subplots.

Subplots are branches of a story that either support or drive the main plot. The Cambridge Dictionary defines subplot as “a part of the story of a book or play that develops separately from the main story.” By including subplots, you add realism to the story you’re telling. Just as events unfold in real life, the reader or viewer doesn’t expect a story to unfold in an exclusively linear manner, but instead to jump around somewhat. That’s what happens when you have a story with subplots.

For the storyteller, the subplots play an important role as a storytelling mechanism. Together with the secondary characters, subplots can be used to do the following:1

- Advance the story in increments

- Unleash transformative forces upon your main character; for example, gain or loss, growth or corruption

- Introduce new information to your main character or the reader

- Pivot the story or provide twists

- Speed up or slow down the story

- Patch holes or solve other problems with your main plot

- Induce mood such as comedy, pathos, triumph, or menace

- Insert or challenge a moral lesson

In many instances, the subplot is tied to the main plot and character by putting an immediate effect on situations or characters. Another way of using subplots is for these secondary stories to run parallel to the main story. Used this way, they add contrast and can, for example, explain decisions made by the main character. They can also be used to add a reminiscing element or backstory without it affecting the main plot. Subplots make the story real and add to the main plot.

The Role of the Main Plot and Subplots in Product Design

Solving problems in the main plot might make you think of main journeys, and alternate ones that users may take if things don’t go as planned; for example, through a forgotten password link, or the need to contact customer support for help. For the product experiences we work on, these subflows and journeys add realism, just as they do in traditional storytelling. They take into account the reality of what it’s like when people use our products. People might forget passwords or need different things from our website, and those users will need to jump between sections to find some background or contact information while learning about what we offer.

In both stories and product experiences, the user or character will also often have more than one thing that requires their time and attention. It’s one of the reasons users seldom complete a task in one go. They might get disrupted or distracted, or intentionally navigate away from our website or app to do research, only to return later. This multitasking is an accurate reflection of how life actually is, so incorporating these details, subflows, and alternate journeys is a necessity for making sure that our product experiences will work and cater to what people need, and what might happen as they use our product or service.2

The need for a user or customer to get in contact with customer support because of a problem is an obvious subplot. But, increasingly, subflows and alternate journeys are also about understanding different combinations of content, touch points, entry and exit points, and how to make the product experience work best no matter the mix. As we covered in Chapter 5, each overarching product experience story is made up of many smaller mini-stories, and each subflow or alternate journey is a story in itself. A story where the “why it began” is a key part.

For the purpose of this book, we’ll use the following definitions for plot and subplots when it comes to product design:

Main plot

The primary journey, either high level or detailed, associated with the desired user journey for the product or service. This plot has to take place for there to be a product or service experience. This can be either the full end-to-end experience journey or parts of it related to a sequence; for example, getting a new phone (full end-to end-journey) or researching buying a new phone (part of the full end-to end-journey).

Subplots

All minor journeys that branch off from the primary journey, either high level or detailed. These can result from the user encountering a problem in relation to the product, being distracted, or making a deliberate decision. These are often referred to as edge cases, alternative paths, non-happy paths, or non-ideal paths; for example, a forgotten password, shopping cart abandonment.

In traditional storytelling, each subplot should impact the main plot, or that subplot doesn’t have a place in that story. In product design, the same is true: all alternate paths, whether happy or unhappy, should have a connection to the main experience.

Types of Subplots

In traditional storytelling, subplots have various types (e.g., romantic, conflict, and expository subplots). Other ways of defining subplots are by the way they relate to the main plot. Here are some examples:3

Mirroring subplots

These mirror the main plot but don’t duplicate it (e.g., a romance that takes place between two secondary characters).

Contrasting subplots

These show the opposite type of progress to the main plot (e.g., a secondary character has the same weakness as the main character, but refuses to go on a journey or through personal development, which in turn benefits the growth of the main character).

Complicating subplots

These represent change and cause problems in the main plot. Contrary to mirroring subplots and contrasting subplots, complicating subplots might not directly relate to the main theme of the story but instead intersect with the main plot in such an important way that they are inextricable from the main plot (e.g., the main character has a task to complete, which is not directly related to the main plot).

What type of subplot you choose should both be relevant to and depend on your main storyline.

Subplots can also consist of different subtypes. For example, there can be a romantic subplot to the main plot, a mystery subplot, a vendetta subplot, or similar. However, some genres don’t lend themselves well to being subplots. Adventures are one example as these tend to be quite large stories in and of themselves and as such are better as main plots.

Having an understanding of the subplot type is important in product design, to help inform the product experience design. While there can definitely be different kinds of subplots, the types used in traditional storytelling aren’t as relevant to product design. Instead, in product design, we propose alternative, unhappy, and branched journey subplots.

Alternative Journeys

Alternative journeys in product design resemble mirroring subplots. In mirroring subplots, the main plot is mirrored but it isn’t duplicated. Here, the key lies in the word alternate, which Cambridge Dictionary defines as “one that can take the place of another.” Alternative journeys are alternative routes that a user may take to reach the same end destination (Figure 10-1).

Alternative journeys depict variations in the way the user comes to making a decision about a purchase. The main plot and journey might be based on what data shows are the key steps that the majority of users currently take from; for example, from first hearing about a product to making a purchase. A subplot will be a secondary or tertiary route that users may take; for example, doing most of their research offline or starting from a secondary or tertiary entry point and proceeding from there.

Figure 10-1

Alternative journeys

A great way to starting thinking about alternative journeys is to define the ecosystem of the product or service. By having a clear understanding of all the touch points that might be involved, the various routes a user’s journey could take start to become clear. Here are some examples of typical alternative journeys:

- Alternative entry points to the same page. For example, one user might start with search and another with social.

- Alternative paths within the product or service. For example, one user might go directly to a product page from the home page, while another might go via Mens/Womens pages and then on to a category page like Jackets and then to a specific jacket’s product page.

Unhappy Journeys

In product design, we always want the outcome to be a happy one. We want to fulfill the user’s need or goal, even if the result is an unhappy outcome for the product, such as canceling a SaaS subscription. If that is what the user wants to do, then completing canceling their subscription constitutes a happy outcome and, hopefully, a happy journey.

When we talk about unhappy journeys as a subplot type in product design, we are referring to those that don’t go the way the users would like them to (Figure 10-2). An unhappy journey may include minor obstacles and frustrations throughout, such as CTAs not being 100% clear, trouble finding what they are after, or a page taking a little too long to load. Or the journey might include a more major event, such as not being able to complete the task they set out to do, the website or app displaying an error, or accidentally ordering the wrong thing.

Figure 10-2

Unhappy journeys

Whether minor or big, unhappy journeys in product design resemble contrasting subplots. The essence of contrasting subplots is that they show the opposite progress, growth, or change than the main plot. Thinking in terms of the opposite of a happy journey/outcome is a great way to identify the unhappy journeys and the major and minor moments they can contain.

While identifying the ideal happy journeys in product design is important for understanding desired paths and outcomes, identifying the alternative paths and unhappy journeys is just as important. As much as we’d like them to, things don’t always go as planned, and for every happy story there is usually at least one possible unhappy outcome, even if just ever so slightly unhappy. To help us avoid the unhappy outcomes as much as possible, it’s important to identify what might lead to an unhappy outcome. Additionally, unhappy outcomes can’t be completely avoided, and for our product and service experiences to deliver, they need to do so under all circumstances, ensuring that we’re always looking after our users and customers.

Branched Journeys

In traditional storytelling, branched narratives are often present when some type of interactive element is present (Figure 10-3). CYOA books are good examples, though defining these as branched narratives is a little too simplistic (because there is more to these types of narratives than that). In video games, the user is faced with making a decision and that decision will then influence the next part of the game experience.

Many of the more functional or interactive types of product or service experiences we work with include elements of branched journeys. To define them, you often need to work with decision tree–based structures to map out the flow of each branch. When working on VUIs and products and services that involve chatbots, decision tree–based structures are a crucial tool for capturing all the scenarios. Bots and voice-based experiences in particular often fall flat when there isn’t a relevant or valuable answer to a user’s query.

Figure 10-3

Branched journeys

The more functional a website or app is, the greater the need for mapping out the full flows, including all the user and system decision points, as well as their results (e.g., a certain screen, error message, etc.). Some of these will result in unhappy journeys/flows, and others in alternative journeys/flows.

Some examples of typical branched journeys are VUIs, bot interfaces, and hotel- and travel-booking websites and apps.

What Storytelling Teaches Us About Working with Main Plots and Subplots

Traditional storytelling teaches us a few key things about plots and subplots that we can apply to product design, including defining and building out subplots as well as visualizing main plots and subplots.

Defining and Building Out Subplots

Just as the main plot should have acts and a clearly defined plot, all subplots should follow a narrative and have all the same elements as the main plot (e.g., an inciting incident and a climax). Rather than happen “on stage” however, subplots occur off stage, and the reader or viewer is often left to put the pieces together themselves.4

In general, subplots will be simpler and not have as many steps involved. They can also vary with regard to when they are introduced and when they are solved (e.g., one subplot being introduced in one chapter and solved in the next), whereas another can run throughout the whole of the main plot. What’s important is that the subplot does get solved and that it impacts the main plot. If it doesn’t, then it shouldn’t be included in the story, as it will then be a separate story altogether.5

When you identify and start to work on subplots, one important point to keep in mind is creating too many subplots will be confusing. There are various ways to come up with your subplots, but one of the most suggested ways is to brainstorm characters who can propel the plot. Writer’s Digest suggests seven ways to come up with your subplot. The following are three ways that have some applicability in product design:6

The isolated chunk

Tell your subplot as a story-within-a-story in an isolated chunk. Don’t worry about transitions, and just start a new section or chapter. This technique can be particularly useful when you write in first-person, as your character can experience only one thing at a time. An example from traditional storytelling is Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In product design, this approach can be useful for subplots in the experience that are independent from the main plot and journey. Unhappy journeys that occur as the experience branches off into a separate journey are one example.

The parallel line

Write a subplot that weaves alongside the main plot. The advice here is to start with your main plot and focus on the main characters, particularly the protagonist. Once it comes naturally, insert the beginning of your subplot, and from there on switch back and forth as evenly as you can, as this will emphasize their symmetrical nature. An example from traditional storytelling is the cat-and-mouse classic The Day of the Jackal by Fredrick Forsyth. In product design, this approach can be applied to alternative paths in particular; though there may be one main path to making a purchase, for example, the different routes can be fairly equal in terms of importance.

The in-and-out

The main plot focuses on one set of characters while the subplot involves other characters. Let your subplots shuttle in and out as needed. For example, a mentor might appear in one chapter, offering some advice, and then disappears on a different journey until returning later in a different chapter. If you write in first-person, it’s perfectly fine for the chapters involving the mentor to be in third-person. In traditional storytelling, an example of this approach is Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Applied to product design, this approach could be applied to any kind of product or service that has recurring characters making an appearance throughout different stages of the experience (see Chapter 6). Ongoing support and unhappy journeys can be one example, but this approach can equally be applied to happy journeys.

How to go about it

If you’ve been involved in defining an overall end-to-end experience, or even just a primary user journey, you’ll have experienced how, inevitably, branching-off points appear. You’ll often know the starting point or the end point and can work your way from there. As with all things, what to do and how to go about it depends on what benefits your project the most. A good starting point is to look at the type of subplot and main plot you’re working with, and based on that, try to identify whether the subplot is best treated as an isolated chunk, a parallel line, an in-and-out. However, keeping to a specific approach is not what’s important. It’s that you’re able to define the subplot.

The preceding approaches from storytelling are simply methods that can help you focus and identify your subplot and how it, if applicable, connects with the main plot.

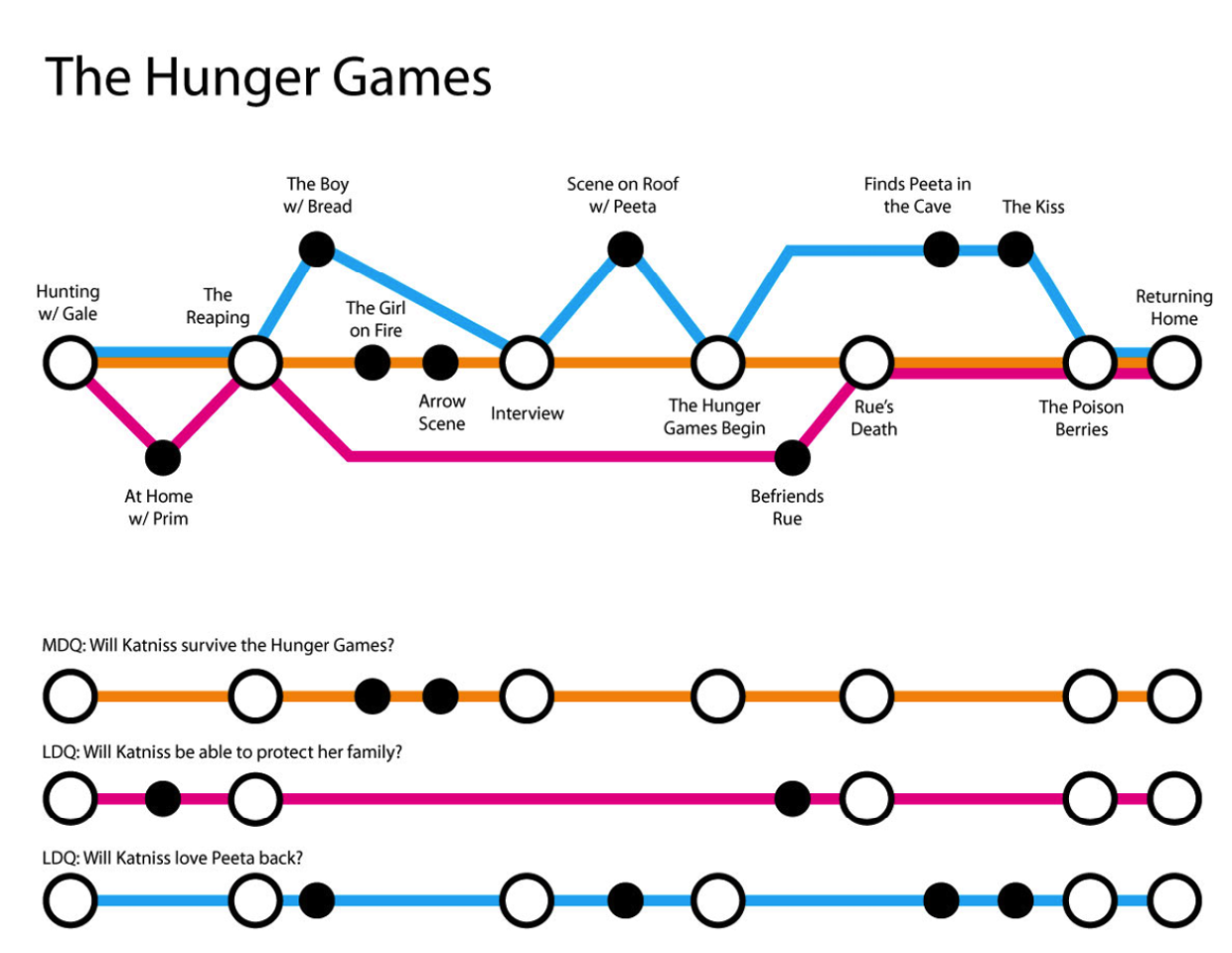

Visualizing Main Plots and Subplots Through Storymaps

We can also turn to traditional storytelling for inspiration when it comes to visualizing the main plot and subplots. Numerous examples can be found online. These storymaps are commonly used to capture the following information:

- An overview of all the subplots

- Where the subplots and the main plot intersect

- What characters are involved in which subplot

Some storymaps, like the one in Figure 10-4, are beautifully done and can both help inform and inspire how we might visualize main plots and subplots in product design. Other provide low-fidelity ways to bring key information to the forefront, something we can also benefit from in the work we do and the way we present it in product design.

Figure 10-4

Storymap of The Hunger Games by Gabriela Pereira DIY MFA7

How to go about it

What to visualize and how will depend on your specific project and what will benefit it the most, but here are some general steps:

- Identify the role and value that visualizing subplots may have. For example, you may use a storymap to show where subplots intersect or to map out the actors and characters involved in each subplot.

- Identify whether this visualization is intended to help you and the team as part of the thinking and defining process, or whether it’s for the client or key stakeholder. This will determine the level of fidelity that you create.

- As with most deliverables, look for inspiration in how others have done it and adapt based on what best benefits your project.

Summary

To some extent we, and more so the users we’re designing for, are lucky that chatbots and VUIs are making an appearance in the products and services that we work on. These types of experiences mean that we have to carefully think through and design for as many eventualities as possible. We’re not quite at the point where we can create a good experience for the user, because dead ends still exist, but these dead ends are opportunities for learning.

Though the primary journey and use case is where we’re placing most of our emphasis, the secondary journeys—alternative paths toward the same destination or unhappy outcomes that have to be dealt with—add realism to the products and services that we design. It’s by actively understanding those that we dig into and understand our users and help root for them to succeed. By capturing what these secondary journeys and subplots are—and where relevant, visualizing how they are all connected—we better understand what’s needed to make the experience come together. That understanding is a prerequisite for what we’ll talk about next: theme and story development in product design.

1 Guest Column, “7 Ways to Add Great Subplots to Your Novel,” The Writer’s Digest, December 17, 2012, https://oreil.ly/pUCZX.

2 Kathy Edens, “How to Use Subplots to Bring Your Whole Story Together,” ProWritingAid, May 17, 2016, https://oreil.ly/jQBE1.

3 Jordan McCollum, “Types of Subplots,” Jordan McCollumn (blog), September 11, 2013, https://oreil.ly/PAoA9.

4 Shawn Coyne, “The Units of Story: The Subplot,” Story Grid, https://oreil.ly/mMMs1.

5 Edens, “How to Use Subplots to Bring Your Whole Story Together.”

6 Guest Column, “7 Ways to Add Great Subplots to Your Novel.”

7 Gabriela Pereira, “How to Create a Story Map,” DIY MFA, May 15, 2012, https://oreil.ly/FbY4p.